Brexit and our shared Digital Cultural Heritage

- Added On: December 5th, 2023

- By: Tam McDonald

- Comments: No Comments

It seems that the tide is more clearly turning against Brexit. This is not just reflecting changing circumstances or opinions, but acknowledges two of life’s great distinctions that, at last, are impressing themselves on a wider British audience. First, simply wanting something doesn’t make it so and, second, grasping the nuances that evolve in the … Read More

Engineering social media in a digital commons

- Added On: November 28th, 2023

- By: Tam McDonald

- Comments: No Comments

Blogging colleague Brad Berens writes in his excellent Weekly Dispatch about the bastardising of the term “social media” by the growing tsunami of effectively anti-social media: doubly egregious as so much of it is not only negative and hurtful in effect but is actually designed to be anti-social. It hitches an ethical ride on the … Read More

First Folio Redux

- Added On: March 28th, 2023

- By: Tam McDonald

- Comments: No Comments

This is not the first time we have blogged about Shakespeare’s First Folio and it won’t be the last. With the quatercentenary of the publication of this famous old book just months away (8 November) we are going to see more celebrations around the world of Shakespeare, most markedly in this week’s convention of the … Read More

Making time for Google Maps

- Added On: March 20th, 2023

- By: Tam McDonald

- Comments: No Comments

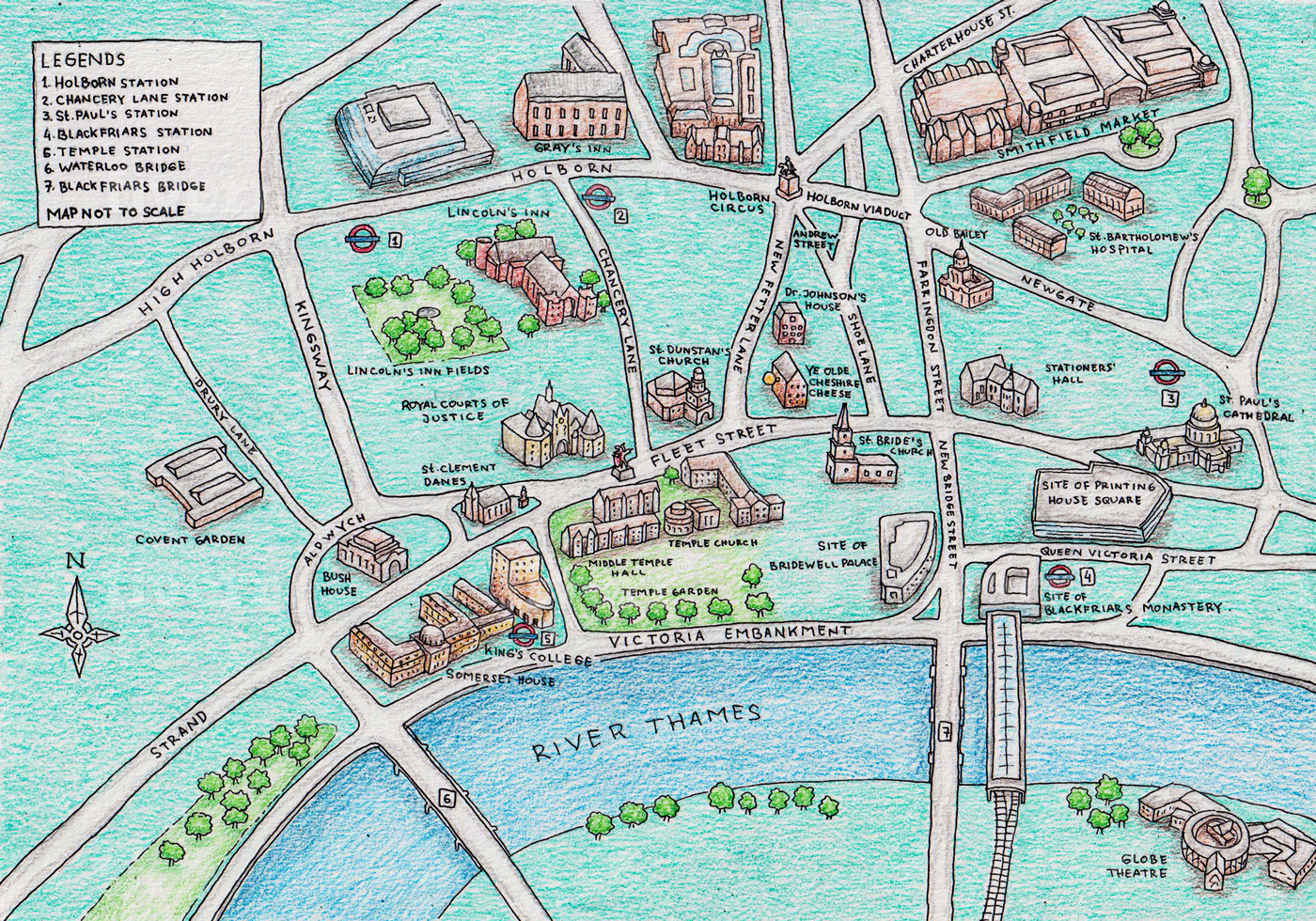

By far the most compelling and visited component of the Cradle of English website, at least until we launched our Crane Court prototype immerzeo, was the home page map itself. The idea was simple enough, and still needs a lot of developing, but the history of the creative heartland of London could scarcely be told … Read More

Foundations of genius

- Added On: December 26th, 2022

- By: Tam McDonald

- Comments: No Comments

Pulsing beneath the surface of our research into the life of William Shakespeare and the publication of his First Folio is the “authorship question”. This “question” is pulsing in the same way that people can still be found who, in the face of evidence and the keenest scholarly research persist in maintaining that the US … Read More

IMMERZEO (2)

IMMERZEO (2) VIDEO GALLERY (7)

VIDEO GALLERY (7)

VIDEO GALLERY

VIDEO GALLERY